Religion in Tolkien's Legendarium

A panegyric of the Professor, and a scan of religious tones (explicit and implicit)

The religious influences of Tolkien’s faith permeate the very seams of Middle-earth. Though there are a few pagans who attempt to read Tolkien’s faith out of his works, this is a minority view; and quite niche at that. I think that Tolkien’s personal writings and actions speak for themselves, but here is a brief examination.

Most everyone has seen the humorous excerpt about Tolkien’s rigid adherence to the Latin version of the Catholic Mass. And everyone is familiar—or ought to be—with at least one very famous and important quote, so we can start off with it. It is from the 142nd letter preserved in The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien. This can provide a sort of first premise, which we can use to understand his editorial choices and private explanations later on. There will be quite a few “repeat” quotes, as a select few serve as incredibly important foundations, and this is certainly one. But to isolate this quote from its greater context would cheapen the intellectual rigor which shines through in everything Tolkien creates.

[Father Robert Murray, grandson of Sir James Murray…and a close friend of the Tolkien family, had read part of The Lord of the Rings in galley-proofs and typescript, and had, at Tolkien’s instigation, sent comments and criticism. He wrote that the book left him with a strong sense of ‘a positive compatibility with the order of Grace’, and compared the image of Galadriel to that of the Virgin Mary. He doubted whether many critics would be able to make much of the book — ‘they will not have a pigeon-hole neatly labelled for it.’]

…

My dear Rob,

It was wonderful to get a long letter from you this morning . . . . . I am sorry if casual words of mine have made you labour to criticize my work. But, to tell you the truth, though praise (or what is not quite the same thing, and better, expressions of pleasure) is pleasant, I have been cheered specially by what you have said, this time and before, because you are more perceptive, especially in some directions, than any one else, and have even revealed to me more clearly some things about my work. I think I know exactly what you mean by the order of Grace; and of course by your references to Our Lady, upon which all my own small perception of beauty both in majesty and simplicity is founded. The Lord of the Rings is of course a fundamentally religious and Catholic work; unconsciously so at first, but consciously in the revision. That is why I have not put in, or have cut out, practically all references to anything like ‘religion’, to cults or practices, in the imaginary world. For the religious element is absorbed into the story and the symbolism. However that is very clumsily put, and sounds more self-important than I feel. For as a matter of fact, I have consciously planned very little; and should chiefly be grateful for having been brought up (since I was eight) in a Faith that has nourished me and taught me all the little that I know; and that I owe to my mother, who clung to her conversion and died young, largely through the hardships of poverty resulting from it.

…

I am afraid it is only too likely to be true: what you say about the critics and the public. I am dreading the publication, for it will be impossible not to mind what is said. I have exposed my heart to be shot at.1

But I think that the religious—and especially Catholic—undertones are more profoundly felt (and seen) in the larger body of Tolkien’s whole Legendarium - and especially in The Silmarillion. Tolkien’s entire mythos stems from a sort of strange stirring of his heart—a sudden inspiration, if you will—which smote him as he read Crist, a trio of poems from The Exeter Book which discuss the advent and life of Christ.

He was particularly interested in extending his knowledge of the West Midland dialect in Middle English because of its associations with his childhood and ancestry; and he was reading a number of Old English works that he had not previously encountered.

Among these was the Crist of Cynewulf, a group of Anglo Saxon religious poems. Two lines from it struck him forcibly:

Eala Earendel engla beorhtast

ofer middangeard monnum sended.‘Hail Earendel, brightest of angels / above the middle-earth sent unto men.’ Earendel is glossed by the Anglo-Saxon dictionary as ‘a shining light, ray’, but here it clearly has some special meaning. Tolkien himself interpreted it as referring to John the Baptist, but he believed that Earendel had originally been the name for the star presaging the dawn, that is, Venus. He was strangely moved by its appearance in the Cynewulf lines. ‘I felt a curious thrill,’ he wrote long afterwards, ‘as if something had stirred in me, half wakened from sleep. There was something very remote and strange and beautiful behind those words, if I could grasp it, far beyond ancient English.’2

Granted, this excerpt is taken further than its proper extent by some. Eärendil is not an allegory for Christ; Tolkien’s disdain for allegory is well-known. The use of éarendel in A-S Christian symbolism as the herald of the rise of the true Sun in Christ is completely alien to my use.3 However, keep in mind the first citation; that “the religious element is absorbed into the story and the symbolism.” On the use of éarendel Tolkien continues:

The Fall of Man is in the past and off stage; the Redemption of Man in the far future. We are in a time when the One God, Eru, is known to exist by the wise, but is not approachable save by or through the Valar, though He is still remembered in (unspoken) prayer by those of Numenorean descent.

Yet still, his conception even in this regard is persistently informed by his Catholic faith. It cannot easily be handwaved that Eärendil stemmed from a mystical inspiration which struck Tolkien in his study of ancient Christian England. Eärendil was the very first character of Tolkien’s mythos. All else stems from the stirring Tolkien felt, that feeling from which Eärendil derived; without which we would not have even The Hobbit.

This notion of the star-mariner whose ship leaps into the sky had grown from the reference to ‘Earendel’ in the Cynewulf lines. But the poem that it produced was entirely original. It was in fact the beginning of Tolkien’s own mythology.4

Eärendil was conceptually formed in 1915, a decade and a half before the construction of The Hobbit had even begun. But I have included this passage for a reason other than to simply establish a chronology: to note the language used to describe the construction of this mythos. Tolkien is not an inventor, but a sort of faerystory archaeologist - unearthing the true spiritual realities of the English past. And all of this is coloured by Tolkien’s Christian view of reality.

G. B. Smith read all Tolkien’s verses and sent him criticisms. He was encouraging, but he remarked that Tolkien might improve his verse-writing by reading more widely in English literature. Smith suggested that he should try Browne, Sidney, and Bacon; later he recommended Tolkien to look at the new poems by Rupert Brooke. But Tolkien paid little heed. He had already set his own poetic course, and he did not need anyone else to steer him.

He soon came to feel that the composition of occasional poems without a connecting theme was not what he wanted. Early in 1915 he turned back to his original Earendel verses and began to work their theme into a larger story. He had shown the original Earendel lines to G. B. Smith, who had said that he liked them but asked what they were really about. Tolkien had replied: ‘I don’t know. I’ll try to find out.’ Not try to invent: try to find out. He did not see himself as an inventor of story but as a discoverer of legend. And this was really due to his private languages.

…

When talking about it to Edith he referred to it as ‘my nonsense fairy language’. Here is part of a poem written in it, and dated ‘November 1915, March 1916’. No translation survives, although the words Lasselanta (‘leaf-fall’, hence ‘Autumn’) and Eldamar (the ‘elvenhome’ in the West) were to be used by Tolkien in many other contexts:

Ai lintulinda Lasselanta

Pilingeve suyer nalla ganta

Kuluvi ya karnevalinar

V’ematte singi Eldamar.

During 1915 the picture became clear in Tolkien’s mind. This, he decided, was the language spoken by the fairies or elves whom Earendel saw during his strange voyage. He began work on a ‘Lay of Earendel’ that described the mariner’s journeyings across the world before his ship became a star.5

Keep in mind that Middle-earth is not a world without Christianity, but a world which exists prior to its realization. This is a story of long ago.6 Tolkien wanted to create a holistic mythology for England.

May you say the things I have tried to say long after I am not there to say them. G. B. Smith’s words were a clear call to Ronald Tolkien to begin the great work that he had been meditating for some time, a grand and astonishing project with few parallels in the history of literature. He was going to create an entire mythology.

The idea had its origins in his taste for inventing languages. He had discovered that to carry out such inventions to any degree of complexity he must create for the languages a ‘history’ in which they could develop.

…

And there was a third element playing a part: his desire to create a mythology for England. He had hinted at this during his undergraduate days when he wrote of the Finnish Kalevala: ‘I would that we had more of it left — something of the same sort that belonged to the English.’ This idea grew until it reached grand proportions. Here is how Tolkien expressed it, when recollecting it many years later: ‘Do not laugh! But once upon a time (my crest has long since fallen) I had a mind to make a body of more or less connected legend, ranging from the large and cosmogonic to the level of romantic fairy-story — the larger founded on the lesser in contact with the earth, the lesser drawing splendour from the vast backcloths — which I could dedicate simply: to England; to my country. It should possess the tone and quality that I desired, somewhat cool and clear, be redolent of our “air” (the clime and soil of the North West, meaning Britain and the hither parts of Europe; not Italy or the Aegean, still less the East), and, while possessing (if I could achieve it) the fair elusive beauty that some call Celtic (though it is rarely found in genuine ancient Celtic things), it should be “high”, purged of the gross, and fit for the more adult mind of a land long steeped in poetry. I would draw some of the great tales in fullness, and leave many only placed in the scheme, and sketched. The cycles should be linked to a majestic whole, and yet leave scope for other minds and hands, wielding paint and music and drama. Absurd.’7

And an absurd goal though it is, he stayed the course. What we are left with is a true English legend. However, the English history seems to be inseparable from its Christian past for Tolkien. Oxford retains an unpublished manuscript of a vast history of the Church in England which Tolkien wrote, echoing Saint Bede. Note: not of the Church of England, but of the Church in England. Tolkien could not separate English history from his Catholic faith, despite the Anglican premises present in England in his age.

But many begin to puzzle: in what way is The Lord of the Rings a “fundamentally religious and Catholic work?” In what way is “the religious element is absorbed into the story and the symbolism?” We can turn here to Tolkien’s Mythopoeia.

This [a discussion with C.S. Lewis about the truth in Christian mystery] was the occasion that led to Tolkien’s writing of “Mythopoeia” (“the making of fables”). There are seven versions of the poem, and according to Christopher Tolkien’s notes it probably was written sometime before 1935. The title of the earliest version was “Nisomythos: a long answer to short nonsense.” None of the versions have addressees, and all have been changed and edited. On the fifth version of the poem, Tolkien wrote “J. R. R. T. for C. S. L.,” and also on the sixth, adding “Philomythus Mismytho” (“lover of myth hater of myth”).

“Mythopoeia” was written in rhyming couplets and contained five primary ideas, which, in a brief compass, expressed Tolkien’s creed of sub-creation and myth. One, God created and controls nature, something he and Lewis already agreed on. Two, language allows humans to name and thus know and experience the world. Three, humans, though “long estranged” and “dis-graced,” are not “wholly lost” and can “draw some wisdom from the only Wise.” Fourth, humans can and should be “subcreators” of truth through myths and stories. And fifth, the assertion that fantasy and myth and “godlike” ideas about beauty are nothing more than “wish fulfillment” (here Tolkien is taking a jibe at one of the prevalent Freudian ideas of his day) is missing the whole point. Tolkien also in this poem expressed his awareness of evil in the world (“...and of Evil this/alone is deadly certain: Evil is”), and that God alone is the “answer” to it.

Joseph Pearce wrote that the final lines of “Mythopoeia” are “Tolkien’s highest achievement in verse,” and picture a vision of Heaven similar to Dante’s Paradiso.8

I would like to briefly point to the way that this shines through in Tolkien’s own mythos, where subcreation occurs. The one Lord of all of creation is Eru Ilúvatar - “alone, the father of all.” Aulë the Vala foretells Tolkien’s Christian views of creating: both in his humility and submission, and also in his deep desire to have wrought.

It is told that in their beginning the Dwarves were made by Aulë in the darkness of Middle-earth; for so greatly did Aulë desire the coming of the Children, to have learners to whom he could teach his lore and his crafts, that he was unwilling to await the fulfilment of the designs of Ilúvatar.

…

Now Ilúvatar knew what was done, and in the very hour that Aulë’s work was complete, and he was pleased, and began to instruct the Dwarves in the speech that he had devised for them, Ilúvatar spoke to him; and Aulë heard his voice and was silent. And the voice of Ilúvatar said to him: ‘Why hast thou done this? Why dost thou attempt a thing which thou knowest is beyond thy power and thy authority? For thou hast from me as a gift thy own being only, and no more; and therefore the creatures of thy hand and mind can live only by that being, moving when thou thinkest to move them, and if thy thought be elsewhere, standing idle. Is that thy desire?’

Then Aulë answered: ‘I did not desire such lordship. I desired things other than I am, to love and to teach them, so that they too might perceive the beauty of Eä, which thou hast caused to be. For it seemed to me that there is great room in Arda for many things that might rejoice in it, yet it is for the most part empty still, and dumb. And in my impatience I have fallen into folly. Yet the making of things is in my heart from my own making by thee; and the child of little understanding that makes a play of the deeds of his father may do so without thought of mockery, but because he is the son of his father. But what shall I do now, so that thou be not angry with me for ever? As a child to his father, I offer to thee these things, the work of the hands which thou hast made. Do with them what thou wilt. But should I not rather destroy the work of my presumption?’

Then Aulë took up a great hammer to smite the Dwarves; and he wept. But Ilúvatar had compassion upon Aulë and his desire, because of his humility; and the Dwarves shrank from the hammer and were afraid, and they bowed down their heads and begged for mercy. And the voice of Ilúvatar said to Aulë: ‘Thy offer I accepted even as it was made. Dost thou not see that these things have now a life of their own, and speak with their own voices? Else they would not have flinched from thy blow, nor from any command of thy will.’ Then Aulë cast down his hammer and was glad, and he gave thanks to Ilúvatar, saying: ‘May Eru bless my work and amend it!’9

The revelations herein are twofold: that creation is the natural desire of the created, but also that it cannot be brought to fulfillment other than in the ultimate creator - that is, God. Nothing can be created which is contrary to God. The Shadow that bred them can only mock, it cannot make: not real new things of its own. I don’t think it gave life to the orcs, it only ruined them and twisted them10 - and Melkor is contrasted with Aulë in precisely this manner.

Melkor was jealous of him, for Aulë was most like himself in thought and in powers; and there was long strife between them, in which Melkor ever marred or undid the works of Aulë, and Aulë grew weary in repairing the tumults and disorders of Melkor. Both, also, desired to make things of their own that should be new and unthought of by others, and delighted in the praise of their skill. But Aulë remained faithful to Eru and submitted all that he did to his will; and he did not envy the works of others, but sought and gave counsel. Whereas Melkor spent his spirit in envy and hate, until at last he could make nothing save in mockery of the thought of others, and all their works he destroyed if he could.11

It is necessary to view the entirety of Tolkien’s Legendarium in this light. In Tolkien’s mind, and in the mind of the investigative reader, it is impossible to separate Tolkien’s wish for an English mythology from the Christian faith which underlies his understanding of reality and the created world. But tolkien was not making a “myth” in the way that the term is often used - and I have intentionally used the term mythos for this reason. Tolkien does not believe that myths are pretty lies: they speak to the depths of our soul and the ungraspable mysteries of reality. This excerpt is, I feel, more important—and certainly more impactful—than even Letter 142. If one were to isolate only one excerpt, I would implore that it be this one:

After dinner, Lewis, Tolkien, and Dyson went out for air. It was a blustery night, but they strolled along Addison’s Walk discussing the purpose of myth. Lewis, though now a believer in God, could not yet understand the function of Christ in Christianity, could not perceive the meaning of the Crucifixion and Resurrection. He declared that he had to understand the purpose of these events — as he later expressed it in a letter to a friend, ‘how the life and death of Someone Else (whoever he was) two thousand years ago could help us here and now — except in so far as his example could help us’.

As the night wore on, Tolkien and Dyson showed him that he was here making a totally unnecessary demand. When he encountered the idea of sacrifice in the mythology of a pagan religion he admired it and was moved by it; indeed the idea of the dying and reviving deity had always touched his imagination since he had read the story of the Norse god Balder. But from the Gospels (they said) he was requiring something more, a clear meaning beyond the myth. Could he not transfer his comparatively unquestioning appreciation of sacrifice from the myth to the true story?

But, said Lewis, myths are lies, even though lies breathed through silver.

No, said Tolkien, they are not.

And, indicating the great trees of Magdalen Grove as their branches bent in the wind, he struck out a different line of argument.

You call a tree a tree, he said, and you think nothing more of the word. But it was not a ‘tree’ until someone gave it that name. You call a star a star, and say it is just a ball of matter moving on a mathematical course. But that is merely how you see it. By so naming things and describing them you are only inventing your own terms about them. And just as speech is invention about objects and ideas, so myth is invention about truth.

We have come from God (continued Tolkien), and inevitably the myths woven by us, though they contain error, will also reflect a splintered fragment of the true light, the eternal truth that is with God. Indeed only by myth-making, only by becoming a ‘sub-creator’ and inventing stories, can Man ascribe to the state of perfection that he knew before the Fall. Our myths may be misguided, but they steer however shakily towards the true harbour, while materialistic ‘progress’ leads only to a yawning abyss and the Iron Crown of the power of evil.

In expounding this belief in the inherent truth of mythology, Tolkien had laid bare the centre of his philosophy as a writer, the creed that is at the heart of The Silmarillion.12

A common question—and often a complaint—is this: if Tolkien’s Christian faith is so important to and foundational in Tolkien’s Legendarium, why is it never explicitly portrayed? One line from the first letter I cited is once again important here: that this element is absorbed into the very essence of the story. Perry Bramlet gives a convincing explanation of this phenomenon.

Tolkien’s attitude toward words and language was very different than most writers and critics of his time, or even our time. He believed that his own art (or pastime) of “linguistic invention” was rare (although he admitted it was for his own pleasure), and that few in his day understood or took the time to try to understand what he was trying to do with words. In his view, words and language stood on their own merits and ordered their own functions. As Tom Shippey wrote, “(modern) critics think that man is master: that poets and artists use words originally, individually, for their own inner purposes. Tolkien feels that words have a life of their own, which continues irrespective of rough treatment from time and careless speakers.”

In a letter to his friend Fr. Robert Murray, Tolkien said that the Lord of the Rings was “fundamentally a religious and Catholic work,” and that he did not put in, or later cut out “practically all references to anything like ‘religion,’ to cults and practices, in the imaginary world.” He added that the “religious element is absorbed into the story and the symbolism,” and that he was grateful to have been “brought up into a Faith that has nourished me and taught me all the little that I know.” And in 1965 W. H. Auden wrote to Tolkien and asked him if the creation of orcs, “an entire race that was irredeemably wicked,” was not heretical. Tolkien replied that he “did not feel under any obligation to make my story fit with formalized Christian theology, though I actually intended it to be consonant with Christian thought and belief . . .”

Although the Lord of the Rings is permeated with the spirit of Christianity and Christian ideals, there is no mention of the Christian God or other gods, no mention of Jesus, no mention of organized religion or its rituals and customs, and no mention of Christianity proper. There are no chapels or churches in Middle-earth, no formal prayers, and no theological writings or pronouncements. Hobbits do get married, but there is no mention of who marries them or where. Tolkien did not tell us where hobbits are buried, and no tombstones or named graveyards are mentioned. Tom Shippey noted that on the Rohan border there is a mountain called Halifirien, which is from an Old English word meaning “Holy Mountain,” but “we never find out who or what it was once holy to.”

But there many hints and allusions to Christian belief in the Lord of the Rings. Frodo is considered by many to be a Christ-like figure, who carried his “cross,” the Ring, to its ultimate destiny. Gandalf often inferred that he believed in a divine providence or power, as when he said that Bilbo was meant to find the Ring, and that this was not a “strange chance.” There are veiled references to immortality in the mention of Aragorn never returning to Cerin Amroth as a “living man” and when Theoden said (the Return of the King) as he was dying, “I go to my fathers.” And there are many others. One author wrote that “(in Tolkien’s story) one can find the themes of justice and mercy, the economy of grace, the persistence of evil, and the demand for hope... any transference of Tolkien's stories to another medium should take into account his Christian intentions... one cannot separate his Christian message from his stories.”13

The simplest answer (or rather, explanation) which can be given is this: that Tolkien has a particular distaste for explicit references in fantasy. If the words of a story have their own life, then beating the reader over the head with their meaning takes away the story’s mystique.

There is of course a clash between ‘literary’ technique, and the fascination of elaborating in detail an imaginary mythical Age (mythical, not allegorical: my mind does not work allegorically). As a story, I think it is good that there should be a lot of things unexplained (especially if an explanation actually exists); and I have perhaps from this point of view erred in trying to explain too much, and give too much past history. Many readers have, for instance, rather stuck at the Council of Elrond. And even in a mythical Age there must be some enigmas, as there always are. Tom Bombadil is one (intentionally).14

And Tolkien’s formalized Legendarium is not unique in this tendency. This feeling is present very early on in Tolkien’s works.

Another major poem from this period [the early 1930s] has alliteration but no rhyme. This is ‘The Fall of Arthur’, Tolkien’s only imaginative incursion into the Arthurian cycle, whose legends had pleased him since childhood, but which he found ‘too lavish, and fantastical, incoherent and repetitive’. Arthurian stories were also unsatisfactory to him as myth in that they explicitly contained the Christian religion. In his own Arthurian poem he did not touch on the Grail but began an individual rendering of the Morte d’Arthur, in which the king and Gawain go to war in ‘Saxon lands’ but are summoned home by news of Mordred’s treachery.15

Tolkien prefers to let his stories speak for themselves. He was, as I mentioned before and which he has mentioned in above citations, infamous for his dislike of allegory. Once more, Tolkien’s mythos can not be wholly isolated from his life or his attitudes. We can see his motivation in not only Mythopoeia, but his other writings as well. As before, Tolkien does not feel that he—or anyone else—is creating something truly new when they weave myths. The attempt to “find it” as mentioned above is an attempt at portraying the nature of the reality. And this reality, Tolkien feels, was created for us by God.

Some have puzzled over the relation between Tolkien’s stories and his Christianity, and have found it difficult to understand how a devout Roman Catholic could write with such conviction about a world where God is not worshipped. But there is no mystery. The Silmarillion is the work of a profoundly religious man. It does not contradict Christianity but complements it. There is in the legends no worship of God, yet God is indeed there, more explicitly in The Silmarillion than in the work that grew out of it, The Lord of the Rings. Tolkien’s universe is ruled over by God, ‘The One’. Beneath Him in the hierarchy are ‘The Valar’, the guardians of the world, who are not gods but angelic powers, themselves holy and subject to God; and at one terrible moment in the story they surrender their power into His hands.

Tolkien cast his mythology in this form because he wanted it to be remote and strange, and yet at the same time not to be a lie. He wanted the mythological and legendary stories to express his own moral view of the universe; and as a Christian he could not place this view in a cosmos without the God that he worshipped. At the same time, to set his stories ‘realistically’ in the known world, where religious beliefs were explicitly Christian, would deprive them of imaginative colour. So while God is present in Tolkien’s universe, He remains unseen.

When he wrote The Silmarillion Tolkien believed that in one sense he was writing the truth. He did not suppose that precisely such peoples as he described, ‘elves’, ‘dwarves’, and malevolent ‘ores’, had walked the earth and done the deeds that he recorded. But he did feel, or hope, that his stories were in some sense an embodiment of a profound truth. This is not to say that he was writing an allegory: far from it. Time and again he expressed his distaste for that form of literature. ‘I dislike allegory wherever I smell it,’ he once said, and similar phrases echo through his letters to readers of his books. So in what sense did he suppose The Silmarillion to be ‘true’?

Something of the answer can be found in his essay On Fairy Stories and in his story Leaf by Niggle, both of which suggest that a man may be given by God the gift of recording ‘a sudden glimpse of the underlying reality or truth’. Certainly while writing The Silmarillion Tolkien believed that he was doing more than inventing a story. He wrote of the tales that make up the book: ‘They arose in my mind as “given” things, and as they came, separately, so too the links grew. An absorbing, though continually interrupted labour (especially, even apart from the necessities of life, since the mind would wing to the other pole and spread itself on the linguistics): yet always I had the sense of recording what was already “there”, somewhere: not of “inventing”.’16

Tolkien’s letters (aside from demonstrating a distinct and cogent understanding of exactly what he was doing in a multitude of ways) show that his understanding of God’s economy of power in the real world is inseparable from his view of his own mythos. It is impossible to read through Tolkien’s letters without seeing the views of a deeply Christian man. It is in fact quite difficult for me to isolate certain quotes, contrary to my impulse to include hundreds of pages’ worth of proof to this fact. But I think that the following quote voices a strong support for this notion.

Suffering and experience (and possibly the Ring itself) gave Frodo more insight; and you will read in Ch. I of Book VI the words to Sam. ‘The Shadow that bred them can only mock, it cannot make real new things of its own. I don’t think it gave life to the Orcs, it only ruined them and twisted them.’ In the legends of the Elder Days it is suggested that the Diabolus subjugated and corrupted some of the earliest Elves, before they had ever heard of the ‘gods’, let alone of God.

I am not sure about Trolls. I think they are mere ‘counterfeits’, and hence (though here I am of course only using elements of old barbarous mythmaking that had no ‘aware’ metaphysic) they return to mere stone images when not in the dark. But there are other sorts of Trolls beside these rather ridiculous, if brutal, Stone-trolls, for which other origins are suggested. Of course (since inevitably my world is highly imperfect even on its own plane nor made wholly coherent — our Real World does not appear to be wholly coherent either; and I am actually not myself convinced that, though in every world on every plane all must ultimately be under the Will of God, even in ours there are not some ‘tolerated’ sub-creational counterfeits!) when you make Trolls speak you are giving them a power, which in our world (probably) connotes the possession of a ‘soul’. But I do not agree (if you admit that fairy-story element) that my trolls show any sign of ‘good’, strictly and unsentimentally viewed.17

In fact Tolkien visualizes even the most deeply layered messages or instincts of his writings, whether about elves or dwarves, through the same lens that he views the obligations of Christians. From the same letter:

I should regard them [the Ñoldor of Eregion] as no more wicked or foolish (but in much the same peril) as Catholics engaged in certain kinds of physical research (e.g. those producing, if only as by-products, poisonous gases and explosives): things not necessarily evil, but which, things being as they are, and the nature and motives of the economic masters who provide all the means for their work being as they are, are pretty certain to serve evil ends.

Tolkien intends for his works to convey their own message, rather than relying on explicit reference to the real world knowledge of the reader, which would destroy the fantastical element of any mythos. His own devotion and faith shines through unfailingly - not unlike the Phial of Galadriel, if you’ll permit me the reference. Peter Kreeft makes a few telling observations which speak to this fact.

Tolkien believed that we too have guardians,…guardian angels. And it is good to know a little about them—but not too much. For, as Pippin says, “‘We can’t live long on the heights.’ ‘No,’ said Merry. ‘I can’t. Not yet, at any rate. But at least, Pippin, we can now see them, and honour them . . . and not a gaffer could tend his garden in what he calls peace but for them, whether he knows about them or not. I am glad I know about them a little’” (LOTR, p. 852). And so are we.

The highest of the “guardian angels” in The Lord of the Rings is Elbereth. At the most critical juncture in the Quest, Sam is inspired to invoke her by name, “speaking in tongues” (language is always the clearest indicator of importance in Tolkien):

A Elbereth Gilthoniel

o menel palan-diriel,

le nallon sí di-nguruthos!

A tiro nin, Fanuilos! (LOTR, p. 712)

This translates as: “O Elbereth Starkindler from heaven gazing-afar, to thee I cry now in the shadow of death. O look towards me, Everwhite.”

Indeed, Tolkien writes, “I am a Christian (which can be deduced from my stories), and in fact a Roman Catholic. The latter ‘fact’ perhaps cannot be deduced; though one critic (by letter) asserted that the invocations of Elbereth, and the character of Galadriel . . . were clearly related to Catholic devotion to Mary” (Letters, no. 213, p. 288). Tolkien introduces Elbereth in The Silmarillion as “Varda, Lady of the Stars, who knows all the regions of Ea. Too great is her beauty to be declared in the words of Men, or of Elves; for the light of Iluvatar lives still in her face. In light is her power and her joy” (Silmarillion, p. 27). He also says of Galadriel: “I think it is true that I owe much of this character to Christian and Catholic teaching and imagination about Mary” (Letters, no. 220, p. 407). And he writes to Fr. Robert Murray, SJ., “I think I know exactly what you mean by the order of Grace; and of course by your references to Our Lady, upon which all my own small perception of beauty both in majesty and simplicity is founded” (Letters, no. 142, p. 172).18

Peter Kreeft continues later, and gives a very effective and focused insight into the way which this worldview plays out in the Legendarium.

Frodo is a Marian figure. His fiat (“I will take the Ring though I do not know the way” [LOTR, p. 264]) is strikingly similar to Mary’s (“Let it be to me according to your word” [Lk 1:38]). They are opposite sides of the same coin: Mary consented to carry the Savior of the whole world, the Christ, to birth, to life; and Frodo consented to carry the destroyer of the whole world, the Ring, the Antichrist, to its death. Mary gave life to Life (Christ); Frodo gave death to Death (the Ring).

We all, like Frodo, carry a Quest, a Task: our daily duties. They come to us, not from us. We are free only to accept or refuse our task—and, implicitly, our Taskmaster. None of us is a free creator or designer of his own life. “None of us lives to himself, and none of us dies to himself” (Rom 14:7). Either God, or fate, or meaningless chance has laid upon each of us a Task, a Quest, which we would not have chosen for ourselves. We are all Hobbits who love our Shire, our security, our creature comforts, whether these are pipeweed, mushrooms, five meals a day, and local gossip, or Starbucks coffees, recreational sex, and politics. But something, some authority not named in The Lord of the Rings (but named in The Silmarillion), has decreed that a Quest should interrupt this delightful Epicurean garden and send us on an odyssey. We are plucked out of our Hobbit holes and plunked down onto a Road. That gives us our fundamental choice between obedience and disobedience. And if life is war, obedience is essential. It is the first virtue for a soldier.19

But Kreeft doesn’t have to guess; Tolkien draws similar parallels himself. Though the Marian parallels are glanced in previous citations, Tolkien does not hesitate to draw Christological parallels either.

If you re-read all the passages dealing with Frodo and the Ring, I think you will see that not only was it quite impossible for him to surrender the Ring, in act or will, especially at its point of maximum power, but that this failure was adumbrated from far back. He was honoured because he had accepted the burden voluntarily, and had then done all that was within his utmost physical and mental strength to do. He (and the Cause) were saved — by Mercy: by the supreme value and efficacy of Pity and forgiveness of injury.

Corinthians I x. 12-13 may not at first sight seem to fit — unless ‘bearing temptation’ is taken to mean resisting it while still a free agent in normal command of the will. I think rather of the mysterious last petitions of the Lord’s Prayer: Lead us not into temptation, but deliver us from evil. A petition against something that cannot happen is unmeaning. There exists the possibility of being placed in positions beyond one’s power. In which case (as I believe) salvation from ruin will depend on something apparently unconnected: the general sanctity (and humility and mercy) of the sacrificial person. I did not ‘arrange’ the deliverance in this case: it again follows the logic of the story. (Gollum had had his chance of repentance, and of returning generosity with love; and had fallen off the knife-edge.)20

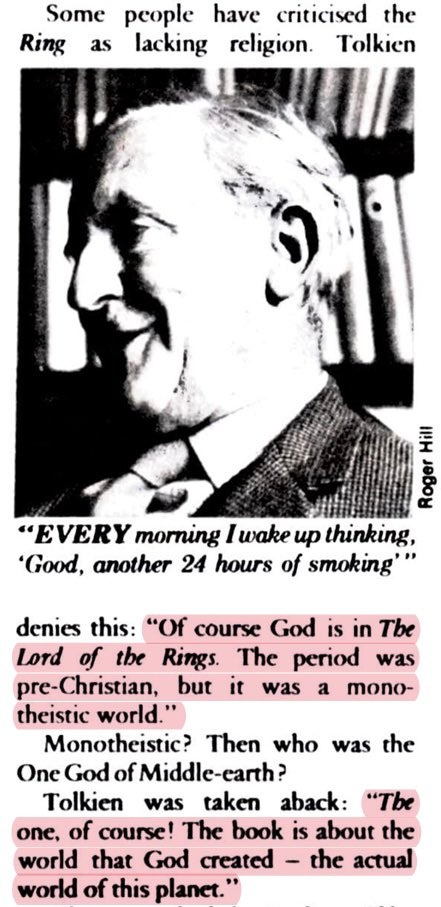

And while this all may seem esoteric, there are many more-explicit indicators. For those who are curious, Tolkien does not refuse answers. This is from an interview with Tolkien, published in the March 22, 1968 edition of the London Daily Telegraph:

Tolkien was overjoyed and profoundly impacted when a reader, engaging with his stories diligently, saw in them a reflection of how Tolkien perceived reality. That is to say, when they glimpsed in his Legendarium the ever-present working of God. This is a humorous and indelibly Tolkien-esque anecdote, but it speaks even more deeply to the compliment paid to Tolkien when a reader grasps the Christian faith present in the mythos which he so diligently weaved.

A few years ago I was visited in Oxford by a man whose name I have forgotten (though I believe he was well-known). He had been much struck by the curious way in which many old pictures seemed to him to have been designed to illustrate The Lord of the Rings long before its time. He brought one or two reproductions. I think he wanted at first simply to discover whether my imagination had fed on pictures, as it clearly had been by certain kinds of literature and languages. When it became obvious that, unless I was a liar, I had never seen the pictures before and was not well acquainted with pictorial Art, he fell silent. I became aware that he was looking fixedly at me. Suddenly he said: ‘Of course you don’t suppose, do you, that you wrote all that book yourself?’

Pure Gandalf! I was too well acquainted with G. to expose myself rashly, or to ask what he meant. I think I said: “No, I don’t suppose so any longer.’ I have never since been able to suppose so. An alarming conclusion for an old philologist to draw concerning his private amusement. But not one that should puff any one up who considers the imperfections of ‘chosen instruments’, and indeed what sometimes seems their lamentable unfitness for the purpose.

You speak of ‘a sanity and sanctity’ in the L.R. ‘which is a power in itself’. I was deeply moved. Nothing of the kind had been said to me before. But by a strange chance, just as I was beginning this letter, I had one from a man, who classified himself as ‘an unbeliever, or at best a man of belatedly and dimly dawning religious feeling . . . but you’, he said, ‘create a world in which some sort of faith seems to be everywhere without a visible source, like light from an invisible lamp’. I can only answer: ‘Of his own sanity no man can securely judge. If sanctity inhabits his work or as a pervading light illumines it then it does not come from him but through him. And neither of you would perceive it in these terms unless it was with you also. Otherwise you would see and feel nothing, or (if some other spirit was present) you would be filled with contempt, nausea, hatred. “Leaves out of the elf-country, gah!” “Lembas — dust and ashes, we don’t eat that.”’21

But I would like to return to one of the letters which Kreeft cites: letter 213. This is perhaps the second most important excerpt, in my opinion.

But, of course, there is a scale of significance in ‘facts’ of this sort. There are insignificant facts (those particularly dear to analysts and writers about writers): such as drunkenness, wife-beating, and suchlike disorders. I do not happen to be guilty of these particular sins. But if I were, I should not suppose that artistic work proceeded from the weaknesses that produced them, but from other and still uncorrupted regions of my being. Modern ‘researchers’ inform me that Beethoven cheated his publishers, and abominably ill-treated his nephew; but I do not believe that has anything to do with his music. Then there are more significant facts, which have some relation to an author’s works; though knowledge of them does not really explain the works, even if examined at length. For instance I dislike French, and prefer Spanish to Italian — but the relation of these facts to my taste in languages (which is obviously a large ingredient in The Lord of the Rings) would take a long time to unravel, and leave you liking (or disliking) the names and bits of language in my books, just as before. And there are a few basic facts, which however drily expressed, are really significant. For instance I was born in 1892 and lived for my early years in ‘the Shire’ in a premechanical age. Or more important, I am a Christian (which can be deduced from my stories), and in fact a Roman Catholic. The latter ‘fact’ perhaps cannot be deduced; though one critic (by letter) asserted that the invocations of Elbereth, and the character of Galadriel as directly described (or through the words of Gimli and Sam) were clearly related to Catholic devotion to Mary. Another saw in waybread (lembas) = viaticum and the reference to its feeding the will (vol. III, p. 213) and being more potent when fasting, a derivation from the Eucharist. (That is: far greater things may colour the mind in dealing with the lesser things of a fairy-story.)22

The phrases which Kreeft singled out are the same ones which I will. Though I feel that the greater context of downplaying even the personal tastes and background of the author are relevant. Tolkien does so in comparison to the (evidently) supreme importance of the context provided by his own religion; but the relationship is twofold. It doesn’t just show that Tolkien sees his imagination as inseparable from his faith - but that he feels that this faith can be deduced from only the material in his stories. And I certainly don’t think that Tolkien was blinded by his faith, unable to see any other way to interpret his stories. Rather, he seems to think that a reader who engages his stories in good-faith will see this. I think this can be seen in the “sanity and sanctity” letter above, but also by actual entrance into the deeply complex world of Middle-earth.

I was particularly interested in your remarks about Galadriel . . . . . I think it is true that I owe much of this character to Christian and Catholic teaching and imagination about Mary, but actually Galadriel was a penitent: in her youth a leader in the rebellion against the Valar (the angelic guardians). At the end of the First Age she proudly refused forgiveness or permission to return. She was pardoned because of her resistance to the final and overwhelming temptation to take the Ring for herself.23

And the Marian tones which Kreeft notes above (and Tolkien acknowledges in his letters) are explicitly addressed in at least one place, along with a more highly elaborated discussion of religion itself in his works. He is here addressing Sam’s cry of A Elbereth Gilthoniel.

As a “divine” or “angelic” person Varda/Elbereth could be said to be “looking afar from heaven” (as in Sam’s invocation); hence the use of a present participle. She was often thought of, or depicted, as standing on a great height looking towards Middle-earth, with eyes that penetrated the shadows, and listening to the cries for aid of Elves (and Men) in peril of grief. Frodo (Vol. I, p. 208) and Sam both invoke her in moments of extreme peril. The Elves sing hymns to her. (These and other references to religion in The Lord of the Rings are frequently overlooked.)

…

In Quenya, however, the simple word fana acquired a special sense. Owing to the close association of the High-Elves with the Valar, it was applied to the “veils” or “raiment” in which the Valar presented themselves to the physical eyes. These were the bodies in which they were self-incarnated. They usually took the shape of the bodies of Elves (and Men). The Valar assumed these forms when, after their demiurgic labours, they came and dwelt in Arda, “the Realm.” They did so because of their love and desire for the Children of God (Erusēn), for whom they were to prepare the “realm.”24

These events in The Lord of the Rings don’t merely seem to be religious in nature. They are. Tolkien wishes to provide not a trail of crumbs, but a framework of truth for those who explore his world. And for all those would-be loremasters who delve into Tolkien’s works, there are a few clearer and more direct indicators.

One explicit Christian reference in the Lord of the Rings deserves notice here. Professor Mike Foster (Illinois Central College, East Peoria, Illinois) studied the Tolkien manuscripts at Marquette University and found a handwritten note by Tolkien at the bottom of one manuscript page. The note said that Frodo and the other eight members of the Fellowship must set off on their quest from Rivendell on Christmas Day. In Tolkien’s calendar, the quest ended on March 25, a date that English medieval tradition held was the original Good Friday, and the day in which the Catholic Church celebrates as the Annunciation of the Angel Gabriel to Mary that she will conceive the savior. Many readers, including scholars, missed this “hidden” reference that displayed Tolkien's Christian sensitivities, but it is just one example from many in the Lord of the Rings.25

But—of course—this isn’t isolated to The Lord of the Rings. As a monotheistic world governed by natural law, the whole of Middle-earth is a myth woven out of the strands of Tolkien’s Christian faith. The lore and the world of The Silmarillion is just as (and perhaps moreso) beholden to this.

As for ‘whose authority decides these things?’ The immediate ‘authorities’ are the Valar (the Powers or Authorities): the ‘gods’. But they are only created spirits — of high angelic order we should say, with their attendant lesser angels — reverend, therefore, but not worshipful*; and though potently ‘subcreative’, and resident on Earth to which they are bound by love, having assisted in its making and ordering, they cannot by their own will alter any fundamental provision. They called upon the One in the crisis of the rebellion of Númenor — when the Númenóreans attempted to take the Undying Land by force of a great armada in their lust for corporal immortality — which necessitated a catastrophic change in the shape of Earth. Immortality and Mortality being the special gifts of God to the Eruhíni (in whose conception and creation the Valar had no part at all) it must be assumed that no alteration of their fundamental kind could be effected by the Valar even in one case: the cases of Lúthien (and Túor) and the position of their descendants was a direct act of God. The entering into Men of the Elven-strain is indeed represented as part of a Divine Plan for the ennoblement of the Human Race, from the beginning destined to replace the Elves.

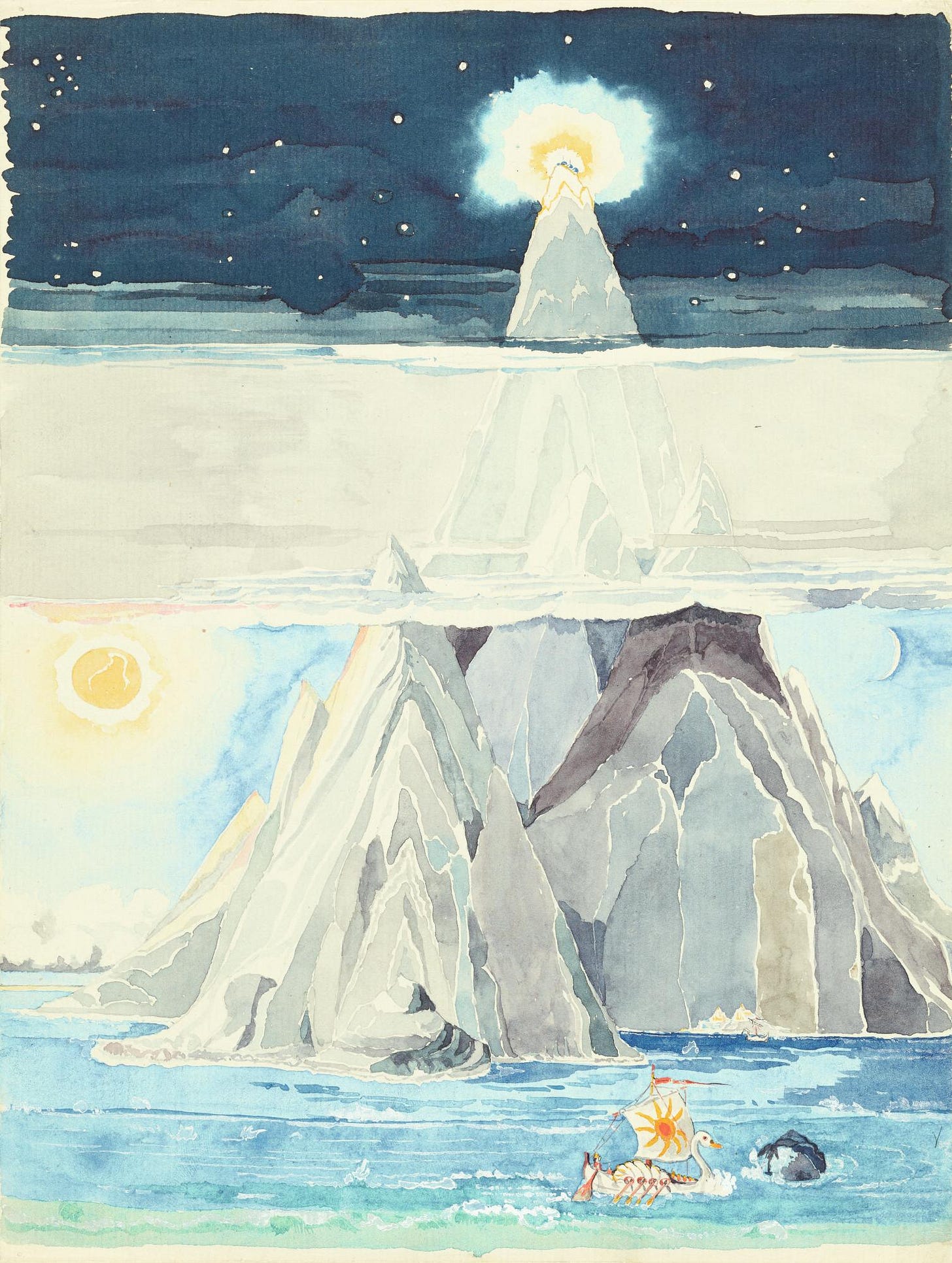

*There are thus no temples or ‘churches’ or fanes in this ‘world’ among ‘good’ peoples. They had little or no ‘religion’ in the sense of worship. For help they may call on a Vala (as Elbereth), as a Catholic might on a Saint, though no doubt knowing in theory as well as he that the power of the Vala was limited and derivative. But this is a ‘primitive age’: and these folk may be said to view the Valar as children view their parents or immediate adult superiors, and though they know they are subjects of the King he does not live in their country nor have there any dwelling. I do not think Hobbits practised any form of worship or prayer (unless through exceptional contact with Elves). The Númenóreans (and others of that branch of Humanity, that fought against Morgoth, even if they elected to remain in Middle-earth and did not go to Númenor: such as the Rohirrim) were pure monotheists. But there was no temple in Numenor (until Sauron introduced the cult of Morgoth). The top of the Mountain, the Meneltarma or Pillar of Heaven, was dedicated to Eru, the One, and there at any time privately, and at certain times publicly, God was invoked, praised, and adored: an imitation of the Valar and the Mountain of Aman. But Númenor fell and was destroyed and the Mountain engulfed, and there was no substitute. Among the exiles, remnants of the Faithful who had not adopted the false religion nor taken part in the rebellion, religion as divine worship (though perhaps not as philosophy and metaphysics) seems to have played a small part; though a glimpse of it is caught in Faramir’s remark on ‘grace at meat’, Vol. II p. 285.426

In another letter, to the same Fr. Robert Murray addressed in the first citation, Tolkien reiterates this (mono)theistic bend in his work.

They [Númenóreans] were given a triple span of life — but not elvish ‘immortality’ (which is not eternal, but measured by the duration in time of Earth); for the point of view of this mythology is that ‘mortality’ or a short span, and ‘immortality’ or an indefinite span was part of what we might call the biological and spiritual nature of the Children of God, Men and Elves (the firstborn) respectively, and could not be altered by anyone (even a Power or god), and would not be altered by the One, except perhaps by one of those strange exceptions to all rules and ordinances which seem to crop up in the history of the Universe, and show the Finger of God, as the one wholly free Will and Agent.

The Númenóreans thus began a great new good, and as monotheists; but like the Jews (only more so) with only one physical centre of ‘worship’: the summit of the mountain Meneltarma ‘Pillar of Heaven’ — literally, for they did not conceive of the sky as a divine residence—in the centre of Númenor; but it had no building and no temple, as all such things had evil associations.27

And to beat a dead horse:

Frodo deserved all honour because he spent every drop of his power of will and body, and that was just sufficient to bring him to the destined point, and no further. Few others, possibly no others of his time, would have got so far. The Other Power then took over: the Writer of the Story (by which I do not mean myself), ‘that one ever-present Person who is never absent and never named’* (as one critic has said). See Vol. I p. 65.

*Actually referred to as ‘the One’ in App. A III p. 317 1. 20. The Númenóreans (and Elves) were absolute monotheists.28

And so as a closing note, I will briefly compare the Ainulindalë—the creation story of Middle-earth and Tolkien’s “Genesis narrative”— to its Scriptural influences:

There was Eru, the One, who in Arda is called Ilúvatar; and he made first the Ainur, the Holy Ones, that were the offspring of his thought, and they were with him before aught else was made.

Compare this with Genesis 1:

In the beginning God created heaven, and earth. And the earth was void and empty, and darkness was upon the face of the deep; and the spirit of God moved over the waters. And God said: Be light made. And light was made.

And with Job 38:

Where wast thou when I laid up the foundations of the earth? tell me if thou hast understanding. Who hath laid the measures thereof, if thou knowest? or who hath stretched the line upon it? Upon what are its bases grounded? or who laid the corner stone thereof, When the morning stars praised me together, and all the sons of God made a joyful melody?

And further:

and a sound arose of endless interchanging melodies woven in harmony that passed beyond hearing into the depths and into the heights, and the places of the dwelling of Ilúvatar were filled to overflowing, and the music and the echo of the music went out into the Void, and it was not void.

Compare this with John 1:

In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God. The same was in the beginning with God. All things were made by him: and without him was made nothing that was made. In him was life, and the life was the light of men. And the light shineth in darkness, and the darkness did not comprehend it.

And further:

Never since have the Ainur made any music like to this music, though it has been said that a greater still shall be made before Ilúvatar by the choirs of the Ainur and the Children of Ilúvatar after the end of days.

Compare this with Apocalypse 14:

And I heard a voice from heaven, as the noise of many waters, and as the voice of great thunder; and the voice which I heard, was as the voice of harpers, harping on their harps. And they sung as it were a new canticle, before the throne, and before the four living creatures, and the ancients;

And finally:

Then Ilúvatar spoke, and he said: ‘Mighty are the Ainur, and mightiest among them is Melkor; but that he may know, and all the Ainur, that I am Ilúvatar, those things that ye have sung, I will show them forth, that ye may see what ye have done. And thou, Melkor, shalt see that no theme may be played that hath not its uttermost source in me, nor can any alter the music in my despite. For he that attempteth this shall prove but mine instrument in the devising of things more wonderful, which he himself hath not imagined.’

Compare this with Genesis 50:

And he answered them: Fear not: can we resist the will of God? You thought evil against me: but God turned it into good, that he might exalt me, as at present you see, and might save many people.

And with Isaiah 64:

And now, O Lord, thou art our father, and we are clay: and thou art our maker, and we all are the works of thy hands.

And with Micah 4:

And now many nations are gathered together against thee, and they say: Let her be stoned: and let our eye look upon Sion. But they have not known the thoughts of the Lord, and have not understood his counsel: because he hath gathered them together as the hay of the floor.

And with Ephesians 1:

In whom we also are called by lot, being predestinated according to the purpose of him who worketh all things according to the counsel of his will.

The heart of man is not compound of lies,

but draws some wisdom from the only Wise,

and still recalls him. Though now long estranged,

man is not wholly lost nor wholly changed.

Dis-graced he may be, yet is not dethroned,

and keeps the rags of lordship one he owned,

his world-dominion by creative act:

not his to worship the great Artefact.

man, sub-creator, the refracted light

through whom is splintered from a single White

to many hues, and endlessly combined

in living shapes that move from mind to mind.

Though all the crannies of the world we filled

with elves and goblins, though we dared to build

gods and their houses out of dark and light,

and sow the seed of dragons, 'twas our right

(used or misused). The right has not decayed.

We make still by the law in which were made.29

https://archive.org/details/lettersofjrrtolk00tolk_1/mode/2up

https://archive.org/details/tolkienbiography0000carp/mode/2up

https://archive.org/details/dli.ernet.474126/mode/2up

https://archive.org/details/iaminfacthobbiti00bram/mode/2up

https://archive.org/details/philosophyoftolk0000kree/mode/2up

https://mindstalk.net/bkxyzzy/tolkien/roadGoesEverOn.pdf

https://www.tolkien.ro/text/JRR%20Tolkien%20-%20Mythopoeia.pdf

Letters, 142

Tolkien: A Biography, p. 64

Letters, 297

Tolkien: A Biography, p. 71

Tolkien: A Biography, ps. 75-76

The Hobbit, Author’s Note

Tolkien: A Biography, ps. 89-90

I Am in Fact a Hobbit, ps. 100-101

The Silmarillion, Of Aulë and Yavanna

The Lord of the Rings, Book VI, Ch. 1

The Silmarillion, Valaquenta

Tolkien: A Biography, ps. 146-147

I Am in Fact a Hobbit, ps. 72-73

Letters, 144

Tolkien: A Biography, p. 168

Tolkien: A Biography, ps. 91-92

Letters, 153

The Philosophy of Tolkien, ps. 75-76

The Philosophy of Tolkien, ps. 204-205

Letters, 191

Letters, 328

Letters, 213

Letters, 320

The Road Goes Ever On: A Song Cycle, ps. 65-66

I Am in Fact a Hobbit, ps. 74-75

Letters, 153

Letters, 156

Letters, 192

Mythopoeia